One of the great engineering feats of modern Australia was the construction of the Sydney Harbour Tunnel.

Page Media:

One of the great engineering feats of modern Australia was the construction of the Sydney Harbour Tunnel.

Page Media:

For more than 100 years, crossing Sydney Harbour via a tunnel had been just a dream. A tunnel had been suggested as early as 1885, when it was realised that ferries were perhaps not the most efficient way to get large numbers of people, carriages and horses across the harbour.

Page Media:

When the Sydney Harbour Bridge was built in 1932, traffic was projected at 13,000 crossings per day. The sort of traffic the designers had in mind included "cars, horses and cattle, pigs and sheep". By 1986, the same number of cars was crossing the bridge in an hour. In 1979, Government called for alternative traffic solutions, including proposals for both bridges and tunnels. All proposals submitted involved the demolition of a large number of dwellings, and were rejected.

Page Media:

In 1984, Transfield was approached by consulting engineers Wargon Chapman Partners to study a solution to building a tunnel without intervention to the inhabited areas to the North and South of the bridge.

Page Media:

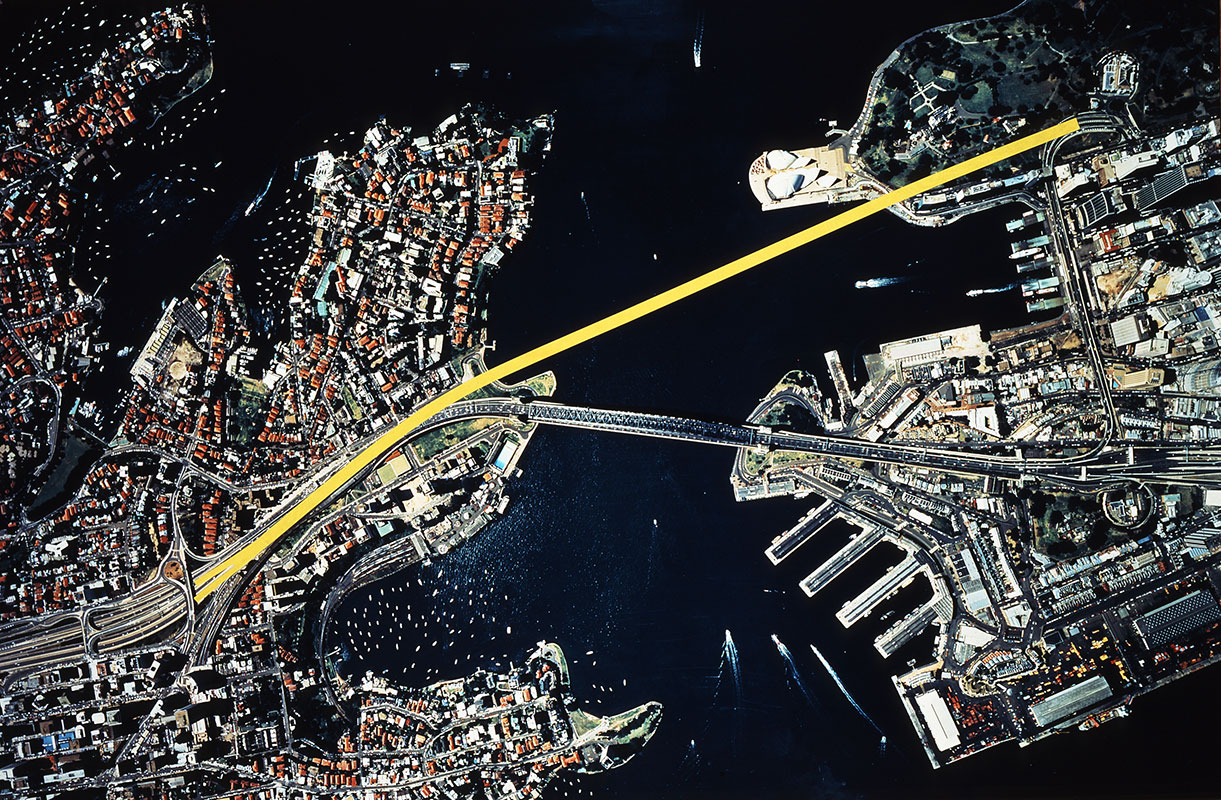

A joint venture was formed with Kumagai Gumi, a large Japanese construction company with extensive experience in tunnel construction and immersed tube technology. In 1986, a crucial meeting took place in the cafeteria at Level 13 of Transfield House in North Sydney, in clear view of Sydney's Harbour Bridge. In attendance were the company executive Tony Shepherd and its consulting accountant, John Scott, engineers Alex Wargon, Reg Hornibrook and Corbett Gore. Kumagai Gumi was represented by Tony Mitani. Alex Wargon laid the plans on the table and all looked out of the window at how the tunnel could be constructed. The solution devised seemed very clever- no buildings needed to be demolished and the new roadtunnel could be incorporated into the existing network on both sides of the harbour. The ventilation stacks were run through the existing northern pylons of the Bridge.

Page Media:

Transfield and Kumagai spent some $4 million developing the proposal as a BOOT- Build Own Operate and Transfer- to privately finance and build the second harbour crossing before getting a commitment from the NSW State Government. With traffic worsening by the day, Cabinet eventually approved the contract in April 1987 amid controversy, as it had been let without the usual tendering process. The decision was taken on grounds that the consortium had invested millions of dollars in preparing the submission. The agreement was signed on 29 June 1987.

Page Media:

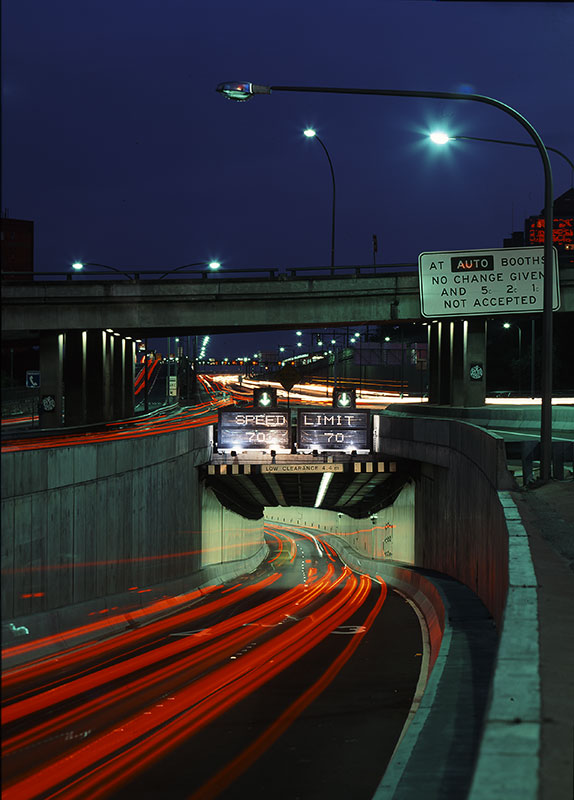

Construction started in February 1988 and the Sydney Harbour Tunnel was officially opened by NSW Premier John Fahey on 29 August 1992. The $750 million tunnel was at the time the largest privately financed infrastructure in Australia.

Page Media:

Technology used for the construction of the tunnel was very advanced for Australia at that time. The eight concrete tube units, each 120 metres long, 26 metres wide and 7.7 metres high, and containing 1370 tonnes of reinforcing steel, were built in Port Kembla, 90 kilometres South of Sydney, floated out of the construction basin and tugged to Sydney Harbour, where they were immersed on site. It was a world-first for reinforced concrete tunnel units of such size being towed in the open sea.

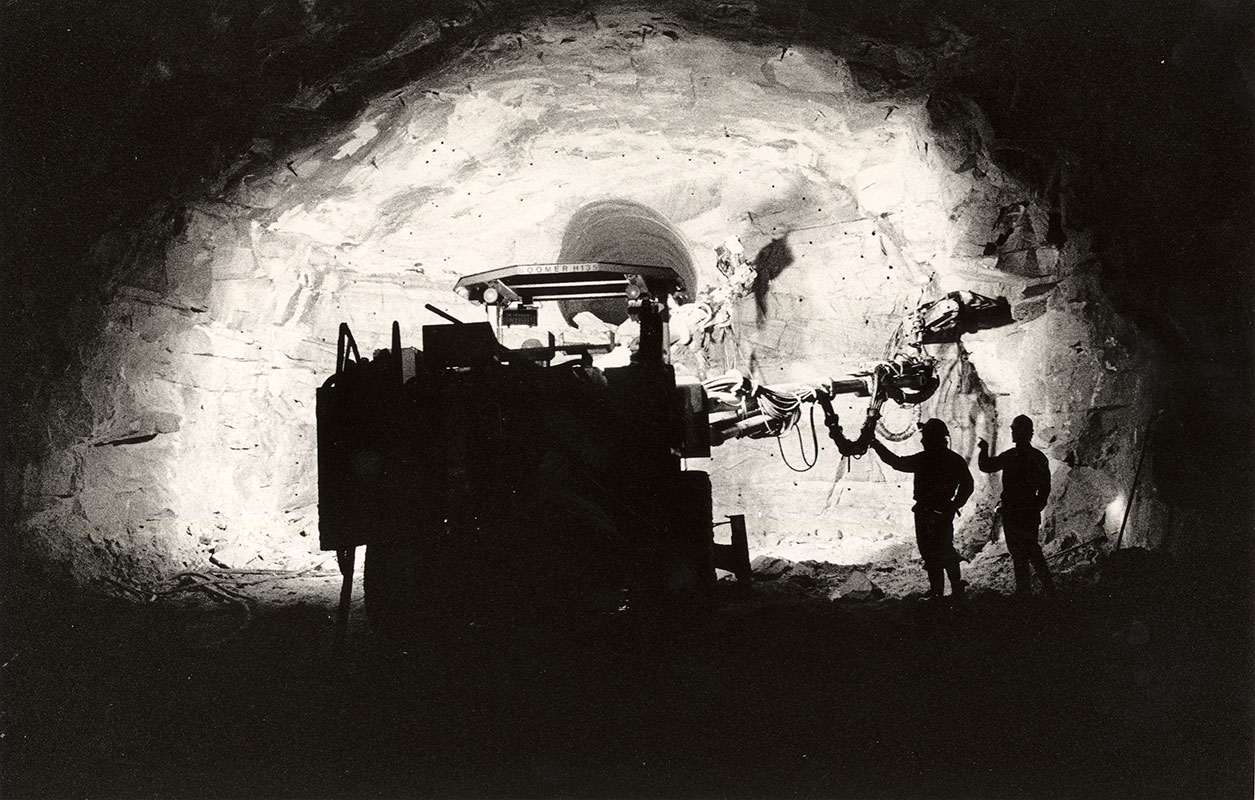

Beforehand, a trench had been dug at the bottom of the harbour, to accommodate the tube units. It took nine months to excavate a total of 700,000 cubic metres of sediment and rock. Dredging was difficult, as the tunnel route crossed the main shipping lanes, constantly used by vessels, ferries and private boats.

Page Media:

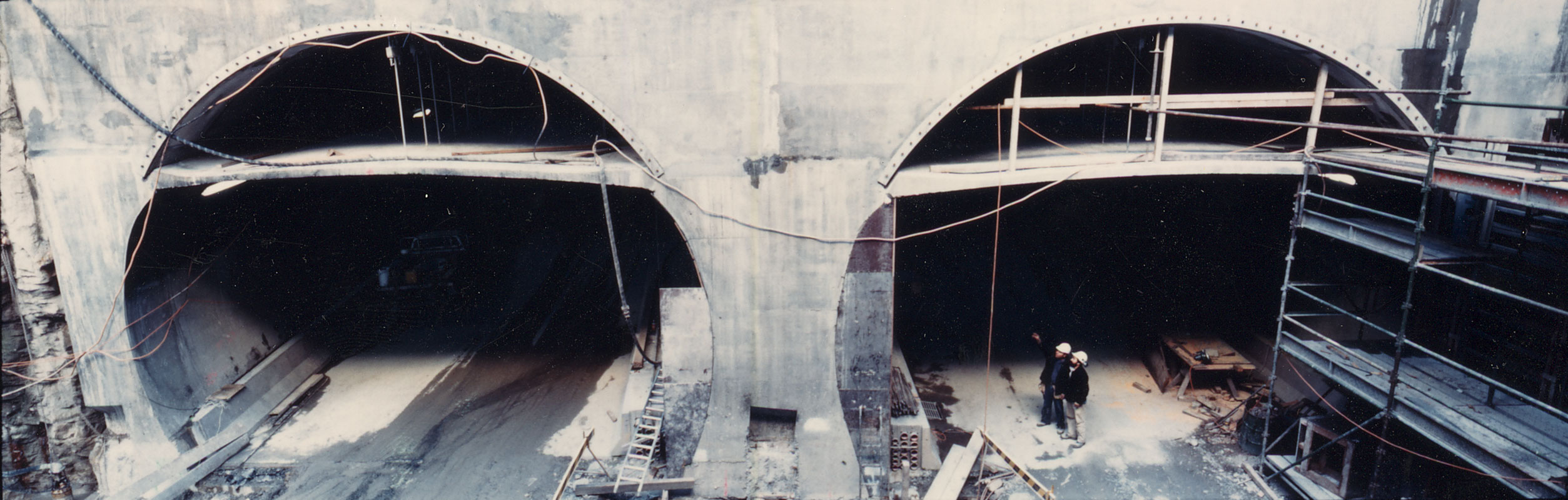

Work on the south shore of the harbour was the most complex and demanding. Beneath the Opera House forecourt, the land-marine transition structure was only accessible by tunnelling, and was constructed entirely underground. A large Moreton Bay fig, its roots just over the tunnel system, had to be preserved at all cost. As excavation was proceeding, the tree root system was propped up from within the tunnel, at a cost of $500k. "It was a bit like watching grass grow", quipped an engineer.

Tunnelling on the northern side of the harbour and excavations for the two ventilation stations presented similarly challenging problems, in particular digging under the sea level and connecting and driving the ventilation systems through and up the two northern pylons of the bridge.

Video: Sydney Harbour Tunnel.

During construction of the concrete units in Port Kembla for the 4-lane, 2.3 kilometre-long tunnel, one million tonnes of water had to be let in and pumped out of the casting basin.

Unlike at the time of the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, when 800 houses had to be demolished, not a single dwelling was lost to make way for the Sydney Harbour Tunnel.

At its deepest point, the tunnel is 27 metres below sea level. 4,500 people were engaged on the project during peak construction.

Page Media:

The consortium operating and maintaining the tunnel, The Sydney Harbour Tunnel Company, comprising Transfield, Kumagai Gumi and Tenix, will hand over to the NSW Government this remarkable infrastructure in the year 2022, and repay the $223 million loan.

Image Gallery: